Pipettes and Popsicles

- Anushka Ring

- Nov 15

- 3 min read

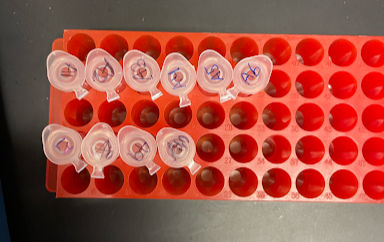

At first glance, the above tubes look similar to popsicle molds, and I wouldn’t blame you for thinking so either. When I saw these tubes I was immediately reminded of the popsicles my mom used to make for me and my brother over long, hot New York City summers while we were growing up. I used to stand by her in the kitchen and watch her make a yummy purple smoothie, pour it into little ice-cream-cone shaped molds in a blue tray, and then put it in the freezer and tell me that I had to wait for them to harden. I watched her over and over until one day I decided that I could do this by myself. Standing on my tip-toes over the kitchen counter, I poured the mixture into the molds and put them in the freezer overnight. Although I had now progressed from blended blueberries and strawberries to the genomes of new fish species, the concept was the same. Put in the molds, wait overnight, results in the morning. This surprisingly artistic photo was taken hastily as an attempt to document my time extracting DNA in the lab while interning at the American Museum of Natural History, and quickly put my phone away so I could get back to our lab work. It had been months of discussing the different characteristics of Congolese fish and talking about all the technicalities behind DNA barcoding, and finally, finally, my mentor had said the magic words: “I think you guys are ready for the lab!” Fish specimens in one hand and notebook in the other, we began the trek down to the museum’s molecular lab. Many admire the architecture of the AMNH and especially the newly renovated Gilder center, which was designed to appear similarly to a honeybee’s hive. What the daily visitors don’t know, however, is that once you get special intern privileges, you spend a lot of time getting to know the dark, scary, underground prison-looking parts of the museum. Rather than inmates, these parts house old anthropology professors, dusty artifacts that were once on view in the late 1800s, and at the end of what my mentor described as “the longest hallway in New York City,” the ichthyology lab. I didn’t really mind getting my steps in as we headed to the lab, because all I could think about was being able to finally extract the DNA from these miniature fish in my hands. As he finally opened the door and welcomed us inside, I stepped in confidently, notes in hand. I was prepared to do this. Immediately, my mentor started ordering us around: “get gloves on!” “clean the blades!” “take out your specimens!” I followed quickly, eager to begin. I picked out two of the fattest fish I could find, which still ended up being half the size of my pinky finger, and set them down on the lab bench. Blade in hand, I said a little prayer for the fish—regardless of it having been dead for about a year now—and sliced it open, taking out little clumps of white tissue. My mentor urged us to get as much as possible, so I wiggled my forceps around the fish’s insides and grabbed anything that I could. I really hoped that this fish, who I had named Jeremiah, was not watching over us. I don’t think he would have found it pleasant. My mentor told us that once we had put the tissue into tubes, we would have to put an enzyme in to dissolve the proteins and incubate the tubes overnight. This was when my mentor gave us the tray of tubes in the orange molds above, and instructed us to put our collected tissue inside. Looking back to those long, care-free summers spent playing at the park and making popsicles, I smiled.

Forget the months of preparation at the museum. Whether it be popsicles or DNA, I had been ready for this since I was nine.

Comments